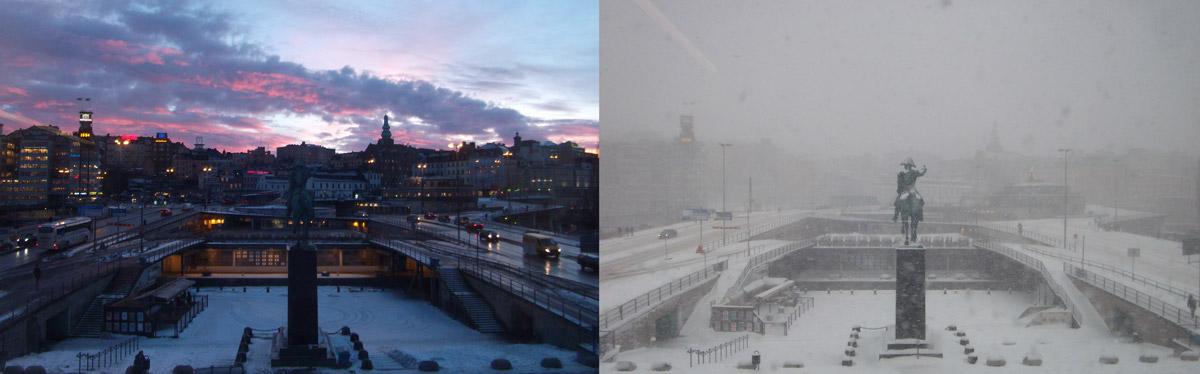

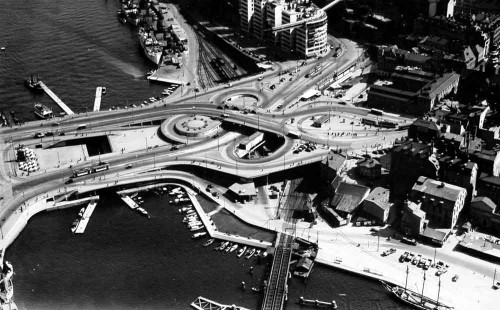

Slussen is a multi-faceted architectural structure in central Stockholm that has functioned as a lock controlling the water level between the lake Mälaren and the Baltic Sea. Slussen is also an important communication hub, hosting an underground station and a bus terminal, and it accomodates local businesses and various forms of socio-cultural life. The current infrastructure was built in the 1930s and has for many years been perceived as an exemplary achievement of modernist thought.

Slussen in the 1930s. Source: Wikipedia.

Due to Slussen’s deteriorating material condition, it will be entirely taken down and, by 2020, become replaced with a new infrastructure. The local businesses, stores, and services contributing to its vibrant identity will ultimately be gone.

Jacek Smolicki started the Slussen Project in 2012 to capture the aural qualities of the architectural infrastructure of Slussen. These recordings are then used to create a virtual environment that will enable anyone to experience the soundscapes of Slussen once the ’real’ setting is gone.

The Slussen Project: Archiving the Aural

Text: Jacek Smolicki, PhD candidate, media and communication studies. This post is a shortened and edited version of the paper ’Ethnographic Research as a Sensory Exploration of Place: The Slussen Project’, soon to be published in the Tsonami 2014 proceedings of the 8th Festival Internacional de Arte Sonoro.

My interest in exploring Slussen was sparked at a time when I started a job at an office located in its vicinity. For almost three years, I passed through the Slussen area at least twice a day. Occasionally, if attracted by some particular situation, I would record a sound sample or speak to some vendors who run their businesses there.

Between December 2012 and May 2013, I visited the area on an almost daily basis. Initially, mapping the soundscapes of Slussen was driven by spontaneous wandering motivated by a sensory attention and intuition, somewhat recalling the practice of a flaneur walking without a goal, at random, abandoning him-/herself to the impressions and sights of the moment. With time, when the space and its soundscapes became more familiar and somewhat controllable, the process became gradually more refined and thus turned from being quite unstructured, intuitive, and serendipitous into being more rigorous and organized.

Intensifying the sense of being present through field recordings

After spotting places that intrigued me with their thick aural quality, I would revisit them equipped with recording tools selected according to the type of the sound, its frequency or intensity. For instance, soundscapes of the harbour area on the eastern side of the complex were recorded using hydrophones that allowed me to capture the underwater acoustics of the lock and movements of boats stationing nearby. To record vibrations of the pillars supporting the railway tracks, I used a self-built contact microphone. Field recording allowed for not only capturing the sounds for further reflection back at the studio, but also let me be more attentively immersed in the actuality of the location I occupied at the time.

’Field recording’ is usually defined as a practice of collecting natural sounds for further use in audio, video or archival production. It can however be considered as not merely connecting the past with the future, but also as a method of intensifying the sense of being present in a given time and space.

The main principle of employing field recording in the Slussen Project was certainly for archiving the aural dimension. However, spending extended periods of time recording, for example, the rhythms of rush hours at the bus terminal – where I would set my microphones and remain still on the ground for more than an hour with my headphones on – indeed let me develop an awareness of the sonic micro-qualities and an ability to notice ephemeral idiosyncrasies, otherwise unnoticeable.

Getting a haircut

Besides walking and field recording, the third important component of my ’sensory ethnography’ was interacting with and interviewing people who have been working in the area, or who were concerned with its history and future.

Initially, I did not have a fixed set of questions to follow, though there were some questions that crystalized throughout the process and to which I have been referring in the following interviews. Such was the question about the one, single aspect of Slussen that: ”if possible, should it be preserved?”.

The first interview I conducted was with an older man, Chrichan, who for over 20 years has been running a small hair salon located in one of the passages. When I visited him for the first time to ask about an interview, he did not seem very pleased, explaining that he has no extra time since he shows up at his little hair salon only if a client pre-books a visit. I decided to book an appointment and came back in a few days, both as a client and an interviewer. After agreeing on a simultaneous interview, I sat down in a chair with my binaural microphones in my ears capturing the conversation we conducted while getting my hair cut. I asked Chrichan about his opinion on Slussen and, just as with many further interviewees, he agreed that the place needed some renovation, though it should not be taken down completely. He pointed out a lack of constructive approach to revitalizing old architecture like it happens, for instance, in Berlin.

Interviewees pointing out places that were interesting

This first interview caused a snowball effect and helped me learn more about the not always visible presence of other actors active within the architectural setting of Slussen. My interviewees were also pointing me to places that they themselves found interesting in terms of sonic and other sensory qualities. Thus, my sensory ethnography can be seen as extended beyond my own observations and reinforced by the sonic sensitivities of the local people. My walking accompanied by the interview subject allowed me to partly ‘sense’ and ‘be’ in the place as it is generated and experienced by him/her.

Traces left on the walls by the members of the motorcycle club at the time occupying one the garages underneath Slussen.

All of my interviewees were following the development of the plans the City of Stockholm had in regard to the area, yet most of those having some kind of an independent business claimed they have been feeling rather confused and ill-informed about their future in the area.

As Bosse, the owner of the record store, expressed, he has ever since opening his little business felt like operating in highly transient conditions. I spent about two hours in his store flipping through vinyl records and eavesdropping on chats he was having with some older men who, as later transpired, were his most regular clients. The music he plays in his little eclectic store dominates the passage nearby, colouring it with mostly rock and funk tunes from the ’50s and ’60s. These sometimes would compete with tango music coming from the neighbouring store with leather goods, and get additionally amplified by the architecture of Blå Bodarna, a famous passage with a blue-painted, circular dome-like structure. Due to its unique acoustic features, this unintended aural phenomenon often inspires improvisation and spontaneity of street performers, conservatory students or drunken youths on weekends.

Blå Bodarna. Source Wikipedia.

The sensory experiences of Slussen will disappear

The modernist architectural infrastructure of Slussen was designed with a clear intention in terms of how it should be used. Over time, however, the modernist thought underlying the organized structure of Slussen has partially dissolved. This dissolution gave room to a variety of other functions and eventually turned the space into an eclectic organism, in which elements at first glance seem highly asynchronous with each other. The current, eclectic identity of Slussen can hardly be evaluated in accordance with the indicators set out with the original plan. Throughout many years, the place has become enriched with many other layers.

Karin Schmidt, a dancer and activist who has been promoting an alternative plan of renovating the existing architecture of Slussen, pointed at different qualities of movement engendered by the place. Just like with many other interviewees, I took a walk with her during which she explained her personal way of experiencing the space. She spoke about the organic principles of movement that are present in the current architecture and which will be missing in the new one. She expressed her concerns about the fact that the most interesting sensory experiences that the current architecture has to offer, such as descending and ascending roads and paths organically binding the movement of traffic and pedestrians – as well as the easily accessible top of one of the circular roofs that presents a 360 degree panoramic view of Stockholm – will disappear completely. During our conversation Karin said that many unique aspects of Slussen, such as the movement it choreographs, are not being acknowledged by stakeholders deciding on the shape of the new architecture, simply due to a lack of competence on their side that would allow such insight. Her voice was yet another among several others calling for an inclusion of artistic competences in evaluating the place.

Recordings enable experiencing the aural dimension of Slussen

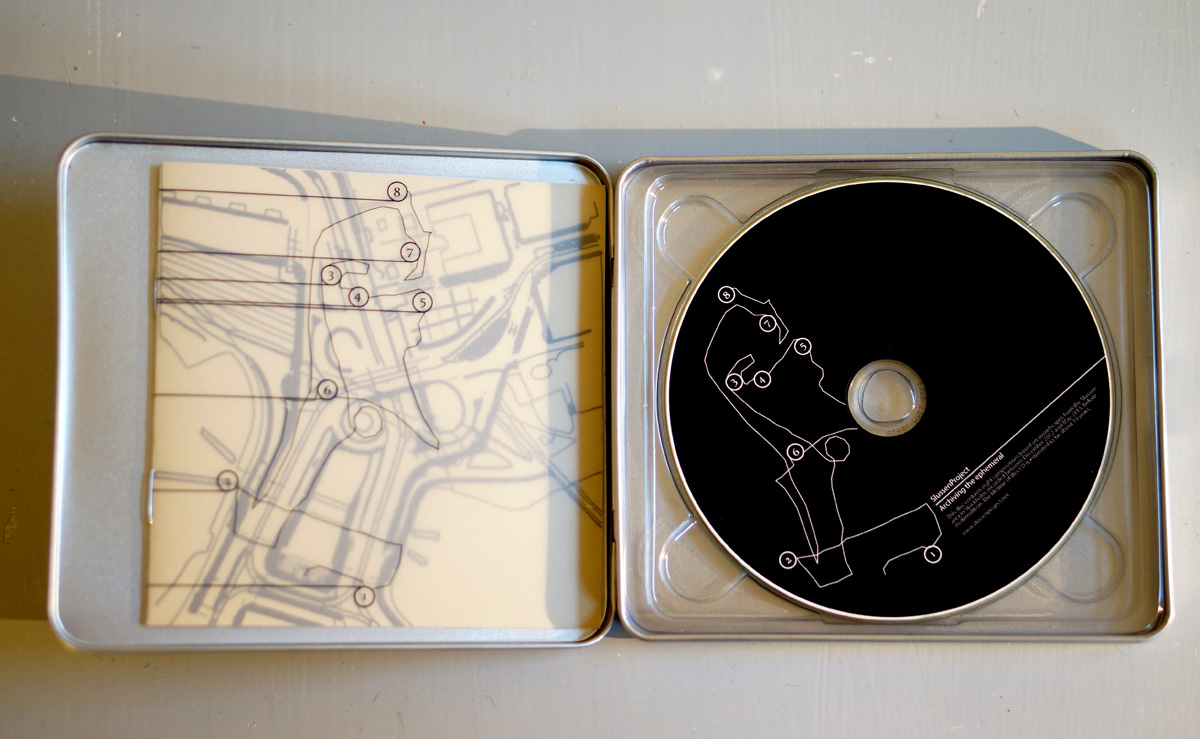

The Slussen Project is continuously under construction. Each composition reflecting each place within Slussen area is composed of several recordings taken there. The basic operations, such as balancing frequencies, volume, and panorama are being applied, but no intrusive effects are imposed. Most of the compositions are 8 minutes long. Every interview is edited and my voice as an interviewer is cut out. All of the collected recordings are intended for being used as a material constituting a virtual environment that will enable to dynamically experience the aural dimension of Slussen once the ’real’ setting is gone. Such mediation of the content, through spatializing it in a virtual – or rather aural – environment, will permit listeners to get more intimately acquainted with the space and facilitate creation of their own exploratory itineraries.

Sound walks are usually pre-recorded narratives guiding users through a specific location. They unfold linearly, leading the listener according to the author’s intention. In the case of the Slussen Project, the intention is that a spatially distributed audio database consisting of a number of the researcher’s findings will invite each listener to take an active role in constructing their own independent narrative. Through walking in a physical space with a mobile phone or other device with a downloaded application, the listeners will have a chance to generate their own soundscapes by physically directing their body towards the chosen source.

Epilogue

One of the activists I interviewed joked saying that she hopes that my archival project will never be implemented since the prerequisite to the appearance of my project is the disappearance of the current Slussen, which she has been strongly defending. In fact, after some resistance from the local communities and activists groups, the process of tearing down some key parts of Slussen has been suspended. Her words however made me think of a certain paradox of a ‘pro-active archiving’, as I would call the Slussen Project. If traditional archiving is about securing the already existing documents, the Slussen Project aims at actively producing a highly idiosyncratic documentation. This documentation is intended to represent the space, to become its replacement. In order to become (re-)presented, it requires the current architecture to be gone. In other words, the life of my Slussen archive, which above all intends to metaphorically save the space and extend its presence, is simultaneously dependent on the death of the actual space. The longer the suspension in tearing down the architecture, the longer the time to think through concerns such as how much the archive enables and how much it disables? How much does it secure and how much does it put at risk?

There is an ongoing discussion on the need to refine the plan and perhaps include some of the objections that proponents of alternative solutions are advocating for. Being detached from the place and currently residing in Malmö certainly affected the method of working on the Slussen Project. However, when in Stockholm, I try to keep track on the debate and occasionally conduct additional interviews. However, the next major step in the project is to start experimenting with a representation of the sonic content spatially.