Urban Gardening is one of the themes that researchers in the Living Archives project are working with. The aim is to explore how cultural-heritage archive material, and open-data sets, can be social resources that support and stimulate urban gardening practices, and contribute to social change and sustainable urban development. This introduction, written by Veronica Wiman gives an introduction the the field of urban gardening and how you can work within it through artistic actions and practices.

Text: Veronica Wiman, curator and professor of contemporary art at Tromsö Academy of Contemporary Art, and guest researcher in the Living Archives project.

We are about 50 Malmö citizens that have a 2×2 meter allotment to cultivate in Slottsträdgården, which is a five-minute walk from Malmö central station. A certain area is designated only for schools and kindergartens. In Sweden, there are in total about 51,000 allotments today, and Malmö was the first city in the country with allotments, as well as with the first community garden. As part of my artistic research, I have taken on this allotment as an experiment to develop knowledge and practices around urban gardening/farming and art. I have invited a group of practitioners (artists, researchers, and a vegan/rawfood chef) to join me in this process. The result after some conversations and decisions is to continue to grow food and to share knowledge and individual expertise. My goal is to create a place for building and sharing knowledge in dialogue with this group of practitioners, but also with other urban gardeners.

My artistic research (in relation to Tromsö Kunstakademiet) has led me to reinvent Tierra Escola, a project developed in collaboration with UN Habitat for the World Urban Forum in Rio de Janeiro in 2009. In brief, the project initially aimed towards an implementation in the city of Rio in collaboration with young women, who had their main income and activities in the streets of Rio. Tierra Escola, an allotment of 3×3 meter, made space for activities such as crafts, planting, and cooking from their harvest. What might seem to be an insignificant gesture for a group of people in the streets of Rio has been moved and contextualized within Malmö and this urban garden/farming research project. The intention is to further develop the Tierra Escola project through a series of public lectures, collaborations with artists and gardeners, and growing vegetables.

Urban gardening: being close and seeing the entire chain

A definition of urban gardening is, according to Uppsala Municipality, a cultivation situated within the city, where production and consumption are geographically close. The definition also includes a perspective of the entire chain: the food we eat, where and how it grows, how it is stored and transported, and finally how the waste is treated. Urban gardening has a mosaic structure, and it is often ecological because you manually handle weeding and composting (instead of using industrial machines), and it is low in energy consumption because of manpower (instead of using fossile-fueled machines).

For decades, agriculture has been almost absent from western cities. Now urban agriculture is becoming a necessity, worldwide. We need a more resource efficient way of living. Climate change urges us to create sustainable cities with more “responsible” values and lifestyles. We need suggestions, experiments, and prototypes from all citizens and practitioners of various fields and backgrounds. The entire world is facing a crisis, and urban agriculture might be a possibility to decrease the vulnerability that lack of food brings.

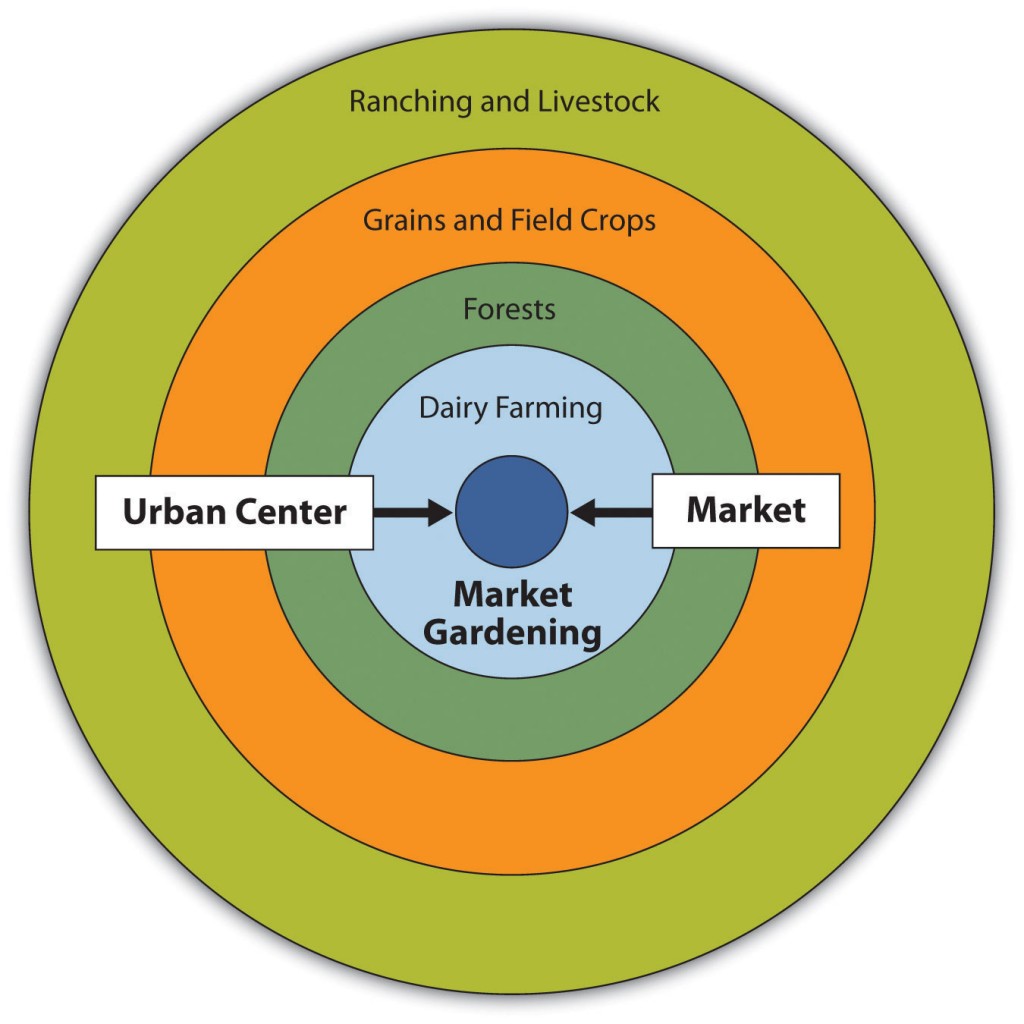

Today we are talking about urban agriculture in new terms as something strategic and infrastructural: “Productive urban landscapes as part of city-planning should be as natural as plumbing in housing” (Gorgolewski, Komisar, and Nasr 2011). Reintegration is an important concept, this since cities have included spaces for cultivation before. Already in 1826, Johann Heinrich von Thünen, a German economist and farmer, described the economic and agricultural relevance of cultivating close to cities. In his model of agricultural land use (see figure below), he presents several ideas that are relevant also today.

According to the recent climate change report (IPCC 2014) there is still time to avoid the worst, and there is political will around the world to do so. Saving energy and reducing emissions is also affordable and economically efficient. What is new in urban agriculture in Sweden, according to Christina Schaffer (Department of Physical Geography and Quaternary Geology, Stockholm University), is the will to take action in response to the climate change, which is a result of failing political initiatives. With this in mind it is encouraging to continue work that might seem and feel like small gestures.

The Planties’ trend

To live in the city, but with a lifestyle as one in the countryside, is a trend in the western world. The daily magazine Metro (Metro 2014, 15) defined the new trend, the Planties’ trend: “A young and ‘aware’ person who doesn’t originally have an interest in gardening or cultivating, but who have started because of an interest in health and environmental concerns”. Analysts claim that the increased interest is due to the uncertainty that climate changes bring, and fear of food with pesticides. Urban gardening is in part a result of a general trend of health awareness in society today.

The report Växttrender (Plantagen 2014) also interprets this as a new “folkrörelse” that has grown during the past 7-8 years: “People have always grown their own food and maybe it is just a short parenthesis when we didn’t”. In Sweden during the early 1900s, when “garden cities” started to develop, the idea was that a family should survive on a 300 square-meter lot to produce potatoes, fruit, and vegetables. Today’s hobby-planting produces a significant amount of food. Last year, Swedes consumed 130,000 tons produce (at an estimated value of 5.4 billion Swedish kronor) from their own allotments, which is equivalent to 9 percent of our total consumption.

Planting as a necessity for survival

In most parts of the world, planting is a necessity for survival. In Havana, Cuba, urban agriculture is a major element of the Havana cityscape and a model for many others with a production growth at 250-350 percent per year (Forsberg 2012). More than 44,000 people work with urban gardens full time. In 2005 they produced 340 grams of vegetables per capita and day, which can be compared to the recommended daily need of 300 gram per day. Ecological small-scale urban farming in order to support the daily food supply of Cuba’s inhabitants was a result of the withdrawal and collapse of the USSR in 1991.

In the city of Bogota, Colombia, Bogota Without Hunger is an effort to face the rapid population growth, nutritional deficiencies, and lack of food supply. Initiated by the city office (and pilot city for the Cities Farming For the Future programme), the urban agriculture project Bogota Without Hunger (RUAF 2007) began in 2004 as a source of food for self-consumption and to promote urban farming as a permanent activity. Through citizen participation, it also aimed to promote environmental conservation, to strengthen the social fabric, and the appropriation of land. Amongst many other activities, led by the Botanic garden, the project focused on native species with high nutritional value to be reintroduced to inhabitants’ diets, as well as on exotic species consumed traditionally.

In Mumbai, India, initiatives of urban gardens on rooftops and organic “farmers’ markets” are increasing. Detroit is famous for having the most (800) community gardens in the western world. With an unemployment rate of 46 percent, the gardens not only supply the inhabitants with produce but also have had positive effect on crime and violence rates.

The City of Malmö has ambitions for urban gardening/farming and it is part of the sustainability plan and various integration projects. A new botanical garden and a new large community urban garden are under development. But the city also has many local private initiatives, run by activists and non-profit organizations. Mykorrhiza is a local network that started out as a guerilla gardening group, but wanted a place where people could meet. Tillväxt is a similar project in Stockholm who claims: “One should not have to buy so much, there should be free fruit, nuts and berries available in public spaces”. They are now in charge of maintaining a few pieces of land in the city. The Association Ätbar Stad is behind “Äppelknyckarmust” and pea cultivations in Lindängen in Malmö.

Focus on artistic actions and practices

In this first phase of my research, I have put emphasis on understanding what the local and global situations and practices of urban gardening/farming are. Within my long-term research, I intend to focus on artistic actions and practices in relation to urban gardening/farming, too study others’, and to develop my own. Since the beginning of this year I have the opportunity to be part of the research team Urban Gardening/Farming within the Living Archives project at Medea, Malmö University, where I am contributing with my expertise and interest in art and artistic practice as a component and source in this field. In March this year, the research team of Living Archives organized the seminar Open Data and Cultural Heritage. We started mapping local and global urban garden practices, archival sources, and the reasons/methods for these initiatives. The main idea is to “prototype for the future” by looking into the history and see how that knowledge can be useful in today’s practices.

Diverse practitioners within urban gardening/farming, perhaps, share the same ends: We want to produce food and contribute to the resilience of our planet and our bodies. But, the processes, the methods, the languages, and the expressions are perhaps quite different between practitioners with an artistic background and practitioners with a gardening background. It is most likely that there will also be differences in describing the success of the work. Artists that inspire me, and which have developed my knowledge and practices, are Amy Franceschini, Marjetica Potrc, and the artist collective Fallen Fruit. Their work draws on many of the aspects seen within urban gardening/farming and combines an activist’s acts with visual production and much more. Their work and projects described give a vast picture of the worlds imagined and created.

References

Forsberg, Björn. 2012. Omställningens tid: Tillväxtens slut och jakten på en hållbar framtid. Karneval förlag.

Gorgolewski, Mark, June Komisar, and Joe Nasr. 2011. Carrot City: Creating Places for Urban Agriculture. Monacelli Press.

IPCC. 2014. Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability.

Metro. 2014. Odlingstrenden växer på balkongerna i stan.

Plantagen. 2014. Längtan att odla och skörda, Växttrender 2014.

RUAF. 2007. Promoting a City without Hunger and Indifference: urban agriculture in Bogotá, Colombia.

Further reading

Amy Franceschini: Victory Gardens.

Civic Matters: International Exchange and Residency Project.

LA Times: San Francisco’s victory gardens project grows a community.

Sydsvenskan: Mer än bara mat.

Tracey, David. 2007. Guerrilla Gardening: A Manualfesto. New Society Publishers.

See also the description of the Living Archives theme Urban Gardening.